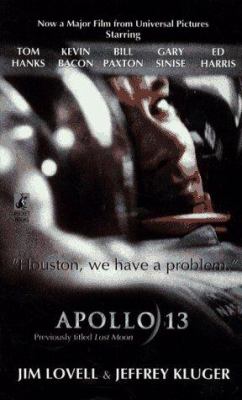

Apollo 13: Lost Moon

Author: Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger

Release: 1994 / 2000

Previously published as Lost Moon

Tagline: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin

Genre: Nonfiction, History, Space Flight, Aerospace, Astronautics

ISBN-10: 0671534645

ISBN-13: 978-0671534646

Synopsis: Out of the seven Apollo expeditions to land on the moon, six of the efforts succeeded outstandingly and one failed. Lost Moon is the story of the failure and the incredible heroism of the three astronauts who brought their crippled vehicle back to earth. This account–written by Jim Lovell, commander of the mission, and his talented coauthor, Jeffrey Kluger–captures the high drama of that unique event and is told in the vernacular of the men in the sky and on the ground who masterminded this triumph of heroism, intellectual brilliance, and raw courage. A thrilling story of a thrilling episode in the history of space exploration.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: “Lost Moon” retitled “Apollo 13” by Jim Lovell & Jeffrey Kluger is an Incredible Read.

Quotes and Lines

“The Apollo 13 spacecraft has suffered a major electrical failure,” he began, “leaving the astronauts in no immediate danger, but ruling out any chance of a lunar landing. Seconds after inspecting the Aquarius lunar module, Jim Lovell and Fred Haise crawled back into the command module and then reported hearing a loud bang followed by a power loss in two of their three fuel cells. They also reported seeing fuel, apparently oxygen and nitrogen, leaking from the spacecraft and also reported that gauges for those gases were reading zero. Mission Control ordered the astronauts to power down the spacecraft, cutting electrical usage while troubleshooters looked for solutions and problems. Without all three fuel cells, the problem becomes getting enough power to fire the spacecraft’s onboard engine to get them back to Earth. Another problem still to be determined is an apparent loss of breathing oxygen in the command module. Mission Control confirms the seriousness of the problem. Repeating, the Apollo 13 astronauts are in no immediate danger, but the flight itself is in danger of being aborted.” -ABC’s Jules Bergman’s first report.

The purpose of the evening was to celebrate the signing of the much debated, prosaically named “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space.” As treaties went, Lovell knew this was not a truly big deal; it wasn’t Versailles, it wasn’t Appomattox, it wasn’t a nuclear test ban. It was one of those treaties that come about because, as the diplomats say, “something should be put on paper.”

Fifteen years earlier, when Lovell was an Annapolis midshipman attending the Army-Navy game in Philadelphia, he met a congenial West Point cadet, whose name he never quite caught, at a crowded hotel party. As was tradition, the friendly foes would exchange makeshift gifts that would serve as mementos of the game and the subsequent celebration. With nothing else handy, Lovell removed one of his Navy cuff links and gave it to the West Pointer; the West Pointer reciprocated with an Army link, and the two young men parted.

More than a decade later, when Lovell had joined the astronaut corps, he told the story to fellow astronaut Ed White. White’s jaw dropped. He was the West Pointer; he, like Lovell, had told the story numerous times over the intervening years, and he, like Lovell, still had the cuff link.

…another pilot in another surveillance plane was taking to the skies over Castro’s angry island to gather a bit more evidence to send back to his president. The pilot of that plane was naval aviator Roger Chaffee.

Lovell kidded Anders when the flight change was made. “Basically,” he said, “we need you to sit there and look intelligent.”

Among the astronauts, many of whom were approaching forty, the Saturn 5 had already earned the sobriquet “the old man’s rocket.” The promised smoothness of the Saturn’s ride, however, was until now just a promise, since no crew had as yet ridden it to space. Within the first minutes of the Apollo 8 mission, Borman, Lovell, and Anders quickly learned that the rumors about the painless rocket were all wonderfully true.

For most of its trip to the moon, the view the Apollo 8 astronauts had was of the distant lunar target growing ever larger in front of them. After leaving Earth orbit, the astronauts took a few rapturous sightings of the receding planet, then turned their spacecraft around to fly in a proper, nose-forward attitude. Strictly speaking, a nose-forward attitude was not necessary in outer space, where Newtonian rules kept a vehicle moving in the same direction no matter where its prow was pointed. But style and custom and a pilot’s taste for tidiness generally dictated a forward-facing ship, so that was how the astronauts flew.

The world laughed itself sick at the West’s debacle, and American newspapers led the charge, ho-ho-ing for days about Yankee ingenuity and its remarkable new “Stayputnik” satellite.

Odyssey he chose because he just plain liked the ring of the word, and because the dictionary defined it as “a long voyage marked by many changes of fortune”–though he preferred to leave off the last part.

But the accident happened 55 hours, 54 minutes, and 53 seconds into the mission…

Within half an hour of arriving at the Marriott, every pilot in Wally’s room had accepted that Project Mercury might well spell the death of his naval career. And every one had decided he’d do whatever he had to do to be a part of it.

Marilyn looked at the scene somewhat incredulously. Weren’t these the same people who had been so conspicuously absent for the last two days? The same ones who didn’t carry her husband’s broadcast last night, who buried the news of his impending launch on the weather page, who gave more time to Dick Cavett’s jokes than to Jules Bergman’s reports?

“If landing on the moon wasn’t enough of a news story for them,” Marilyn said, “I don’t know why not landing on the moon should be. You tell the networks that they’re not to put one piece of equipment on my property from now through the end of this flight. And if anyone has any problem with that, tell them they can take it up with my husband. I’m expecting him home on Friday.”

“Freddo,” Lovell said, turning to Haise, “I’m afraid this is going to be the last moon mission for a long time.”

With Aquarius’s microphones switched to vox, the commander’s forlorn observation drifted 200,000 miles, into the heart of Mission Control and, from there, out into the world.

In principle, every man in room 210 understood that engineering corners would have to be cut if the command module was going to make it home intact. In practice, however, nobody wanted to think that it would be his corner that would be affected…

…one of the most important things an astronaut’s wife needed to remember during the course of a flight was how to ration her reactions. Though the networks could afford to dramatize every tweak of a thruster or torque of a platform for the TV audience, the people whose fathers and husbands and sons were riding inside the spacecraft did not have that freedom. For them, the flight wasn’t national news; it was, in the most literal sense, domestic news. It wasn’t the future of the nation that rode on the outcome, but the future of the household. With stakes that high, the wives, at least, could not afford the luxury of a fully emotional response at each critical turning point.

“Do you believe the law of averages operates with you after all these flights? Do you worry about getting stuck on the moon, for example?”

“No, I kind of feel that every time we make these flights we count on two things. First of all, you’ve got to be well trained to handle emergencies. That’s like money in the bank. Second, you’ve got to remember that every time you go, it’s like a new roll of the dice. It’s not like something that accumulates so that you’re bound to get a seven after a while. You start out fresh every time.”

“Gentlemen!” he said in a voice deliberately too loud for the tiny cockpit. “What are your intentions?”

Startled, Haise and Swigert spun around. “Our intentions?” Swigert said.

“Yes,” said Lovell. “We have a PC+2 maneuver coming up. Is it your intention to participate in it?”

There were a lot of reasons, Lovell decided, that the electrodes had to go. First of all, they itched. The adhesive used to hold the sensors in place was supposedly hypoallergenic, but after four days, even the most skin-friendly glue was going to become annoying, and this glue most assuredly had. More important, pulling off the sensors would save power. The biomedical monitoring system that beamed the astronauts’ vital signs to Earth drew its juice from the same four batteries that powered everything else aboard the LEM, and although the electrodes were hardly power gobblers, they still consumed their share of amps.

“…And just for historical purposes, we note that in the original flight plan, Aquarius would have landed on the moon, with Lovell and Haise aboard, nine minutes ago. In all the excitement, we’ve also forgotten that this is the day that Ken Mattingly was supposed to get the measles. He has not.” from a CBS report by David Schumacher

Since the experiments were intended to operate for well over a year, and since fuel cells or batteries could not keep them running that long, the equipment was instead powered by a miniature nuclear reactor, fueled by spent uranium taken from nuclear power plants.

The thin yellow sheet Kelly had been passed was a copy of an invoice that Grumman would send to another company when Grumman supplied it a part of service. In this case, the company being billed was North American Rockwell, the manufacturer of the command module Odyssey.

On the first line of the form, underneath the column headed “Description of Services Provided,” someone had typed “Towing. $4.00 first mile. $1.00 each additional mile. Total charge, $400,001.00.” On the second line, the entry read: “Battery charge, road call. Customer’s jumper cables. Total $4.05.” The entry on the third line: “Oxygen at $10.00/lb. Total, $500.00.” The fourth line said: “Sleeping accommodations for 2, no TV, air conditioned, with radio. Modified American Plan with view. Prepaid. (Additional guest in room at $8.00/night.”

The subsequent lines included incidental charges for water, baggage handling, and gratuities, all of which, after a 20 percent government discount, came to $312,421.24.

“Marilyn, this is the president. I wanted to know if you’d care to accompany me to Hawaii to pick up your husband.”

Marilyn Lovell paused absently and smiled into the middle distance, picturing the spacecraft she had just seen bobbing on the waters of the South Pacific. The line from Washington crackled slightly.

“Mr. President,” she said at last, “I’d love to.”

As aviators and test pilots had discovered since the days of cloth and wood biplanes, cataclysmic accidents in any kind of craft are almost never caused by one catastrophic equipment failure; rather, they are inevitably the result of a series of separate, far smaller failures, none of which could do any real harm by themselves, but all of which, taken together, can be more than enough to slap even the most experienced pilot out of the sky. Apollo 13, the panel members guessed, was almost certainly the victim of such a string of mini-breakdowns.

Like many nonfiction books of this kind, one of the authors was also one of the participants in the history being recounted; unlike many books of this kind, Lost Moon is written in the third person. Had the key events of the Apollo 13 mission taken place exclusively in the spacecraft, a first-person account, in the singularly well-informed voice of the commander of the mission, would have made the most narrative sense. But as the men and women who were involved in the flight uniformly agree, the tale of Apollo 13 was one with many venues. For this reason, we have tried to take the reader to as many of those places as possible–newsrooms, conference rooms, homes, hotels, factories, naval vessels, offices, ready rooms, laboratories, and of course Mission Control and the spacecraft themselves. To achieve this kind of omniscient sweep, the third-person voice seemed the only way to go.