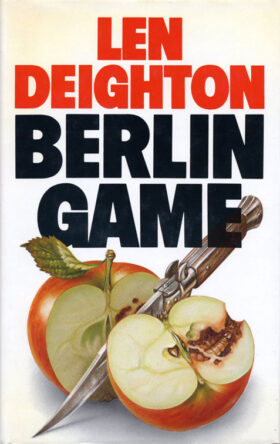

Berlin Game

Author: Len Deighton

Release: January 1, 1985

Publisher: Alfred A. Knopf

Genre: Fiction, Spy Fiction, Espionage

ASIN: B00PACESUQ

Main Character: A Bernard Samson Adventure

Synopsis: The first installment of the Berlin Game, Mexico Set, London Match trilogy.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Meeting Bernard Samson: A No Spoilers Review of Berlin Game by Len Deighton

Quotes and Lines

“Maybe they know things we don’t know,” said Werner.

“You’re right,” I said. “They know that the service is run by idiots. But the word is leaking out.”

I found their sort of conjecture exasperating. It was the stuff of which long memos are made, the paperwork under which the Department is buried. I said, “What’s the use of my guessing? Everything depends upon knowing what he is doing. He’s not a peasant, he’s a scholarly old man with an important and interesting job. We need to know whether he’s still got a happy marriage, with good friends who make speeches at the birth celebrations of his grandchildren. Or has he become a miserable old loner, at odds with the world and needing Western-style medical care. . . . Or maybe he’s just discovered what it’s like to be in love with a shapely eighteen-year-old nymphomaniac.”

My father used to say, “Eternal paranoia is the price of liberty. Vigilance is not enough.”

I always sleep face downward; it stays dark longer that way.

Fiona laughed. “You were always using Latin tags when I first met you. Now you don’t do that anymore.”

“I’ve grown up,” I said.”

“Don’t grow up too much,” she said. “I love you as you are.”

“When you’ve been with the Department for over twenty years and the probationers are calling you Bernie,” I said, “you start thinking that maybe you’re not going to end up as Director-General.”

It was part of my job to guess what frightened a man, and then not to dwell on it but rather let him pick at it himself while I talked of other, tedious things, giving him plenty of opportunity to peel back the scab of fear and expose the tender wound beneath.

I’d been trying to read other people’s minds for most of my life. It could be a dangerous task. Just as a physician might succumb to hypochondria, a policeman to graft, or a priest to materialism, so I knew that I studied too closely the behavior of those close to me. Suspicion went with the job, the endemic disease of the spy. For friendships and for marriages it sometimes proved fatal.

Bret Rensselaer liked to describe himself as a “workaholic.” That this description was a tired old chicken didn’t deter him from using it. He liked cliches. They were, he said, the best way to get simple ideas into the heads of idiots.

Did you ever say hello to a girl you’d almost married long ago? Did she smile the same captivating smile, and give your arm a hug in a gesture you’d almost forgotten? Did the wrinkles as she misled make you wonder what marvelous times you’d missed? That’s how I felt about Berlin every time I went back there.

“There’s no fool like an old fool…”

“We all thought you’d grow up to become a gangster…”

“He always said that the job of the Berlin Resident is to insure that London is not buried under an avalanche of unimportant material. Getting intelligence is easy, Frank said, but sorting it out is what matters.”

“I’ve been taking things too seriously for years,” I said. “I’m afraid it makes me a difficult man to live with. But I’ve stayed alive, sweetheart. And that means a lot to me.”

“Embarrass the KGB! Is that the word he used? They put sane dissidents into lunatic asylums, consign thousands to their labor camps, they assassinate exiles and blackmail opponents. They must surely be the most ruthless, the most unscrupulous, and the most powerful instrument of tyranny that the world has ever known. But dear old Chlestakov is frightened you might embarrass them.”

“You can’t have everything,” I said. “You can’t have the fantasies and the reality. You can’t have the best of both worlds.”

“You’re always in time for the coffee,” said Trent. He was standing at a wooden bench. Upon it there was a bottle of Jersey milk, a catering-size tin of Sainsbury’s powdered coffee, and a bag of sugar from which the handle of a large spoon protruded. Trent was pouring boiling water from an electric kettle into a chipped cup with the name Tiny painted on it in nail varnish. “No matter how long I wait for you, the moment I decide to make coffee, you arrive.”

“Ever wonder why the Berlin Wall follows that absurd line?” said Frank. “It was decided at a conference at Lancaster House in London while the war was still being fought. They were dividing the city up the way the Allied armies would share it one they got here. Clerks were sent out hotfoot for a map of Berlin but the only thing Whitehall could provide was a 1928 City Directory, so they had to use that. They drew their lines along the administrative borough boundaries as they were in 1928. It was only for the purposes of that temporary wartime agreement, so it didn’t seem to matter too much where it cut through gas pipes, sewers, and S-Bahn or these underground trains either. That was in 1944. Now we’re still stuck with it.”

He’d recovered from his self-doubts of the night before, as all soldiers must renew their conscience with every dawn.

“…Sometimes there has to be a really bad disagreement before two people understand each other.”

“Let me do the worrying, Werner,” I said. “I’ve had more practice.”

“Drinking makes you bad-tempered,” said Werner.

“No,” I said. “It’s having the bottle taken away that does that.”

“…I’m always a pessimist. Is your wife a pessimist?”

“She had to be an optimist to marry me,” I said.

Perhaps all fear is worse than reality, just as all hope is better than fulfillment.