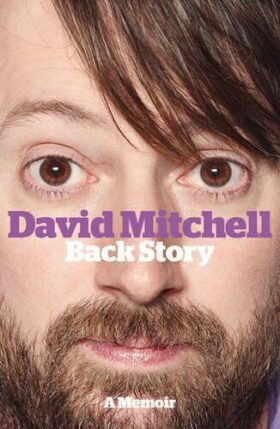

David Mitchell: Back Story

Author: David Mitchell

Release: 2012

Tagline: A Memoir

Publisher: HarperCollins

Genre: Biography, Autobiography, Entertainment, Comedy, Philosophy

ISBN-10: 0007351720

ISBN-13: 978-0007351725

Synopsis: The autobiography of David Mitchell from youth to television personality and author.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: An Authentic “Back Story: A Memoir” by David Mitchell

Quotes and Lines

And I make a very good living doing something I love, a state of affairs that tends to be envied by those who don’t share it.

My childhood self would hate where I live now. He would also be disappointed that I’m not ruler of the world or at least Prime Minister or a wizard.

Maybe everyone is fearless in infancy and what marks us apart is our ability to absorb fears – some of us are made of sponge and soak them up while others are resistant willows that have to be repeatedly painted with the linseed oils of caution to prevent cracking from the dehydrating effect of their own imprudence. And, before you ask, no I haven’t lost control of the metaphor: I’m saying some people are thoughtful, sensitive types like me while others are wooden-headed idiots as a result of whom every foodstuff has to carry an over-cautious ‘Use by’ date. I think I should bloody sue.

…most very small children have in their psychological make-up many of the personality traits of the tyrant and the megalomaniac.

There’s got to be a nasty or dangerous side to anything enjoyable or there’s something wrong, something suspicious and hidden.

We do not, sadly, live in a society that values teaching very highly as a profession. We live in a society that pretends to, but gives the big money to footballers and bankers (and more to comedians and actors than they are probably worth, I’m very happy to admit, but personally I’m in it for the disproportionate praise).

Dark or light, satirical or wacky, message-bearing or surreal, comedians are just fools capering for a king’s pleasure.

…my overwhelming emotion was of having averted disaster – which, if anything, feels better than a triumph.

…the main thing you learn from this whole process is how much entertaining people, telling them a story, moving them, making them laugh, is about instinct and luck.

But, yes, I try to analyse things rigorously – partly because that’s a good approach to life in general and partly because it’s easier to find comic angles that way than by trying to nudge myself into flights of surreal invention.

I still get drunk occasionally, but not very often. I wouldn’t deny a certain sort of social dependence on it, but I think it’s a dependence I share with most of our culture. This society doesn’t work without booze – our parties aren’t good enough, our conversations aren’t sufficiently interesting, nor is our self-confidence high enough to sustain our interactions without alcohol. It’s everywhere, lubricating everything.

In self-pitying moods, I feel like the iPhone, Twitter, Facebook and the battery-operated doorbell are all conspiring to make this the worst time in history to become famous.

In my experience, if you want to write comedy, you just have to get on with it. You have to crash through the invisible barrier cause byu the combination of the vast sense of possibility – a sketch could be about anything, could be the wackiest, most surreal, yet most satirical, wide-ranging, specific, general, flippant, profound piece of material ever written – and the terrifying, narrowing, diminishing feeling caused by scratching the first inadequate words of it onto a sheet of A4. As soon as you start to write, you also start to close doors (metaphorical ones as well as the one to the shop where the sketch is inevitably set).

I think it’s illustrative of an interesting and maddening phenomenon in creative circles: fundamentally unentertaining people trying to make things like other things that have gone before. They believe that properly creative people, who actually have ideas, will try and drag a project off track. So, a student sketch show would have a wacky name, a TV programme should being with the host saying: ‘This is the show in which …’ and then summarising the format, a pop song should be three minutes long, people will be more entertained by daytime TV if the presenters constantly use puns, a TV detective should always have an assistant who relentlessly questions his judgement and books should be described on their covers as ‘rollercoasters’.

Conventions like these are clung to and defended by people who have no real ideas of their own, and lack the self-knowledge to forge careers using other skills such as their efficiency, diplomacy or application. They want to make things that are like other things – to ‘play shop’, which means you’ve got to have a till and a brown coat and a counter with a shelf of tins behind it like in real shops. When they hear something that diverges from that – say a series of aisles with all the produce and then a bank of checkouts where people pay – they instinctively oppose it because they can seldom tell the difference between a properly original piece of thinking and a mad divergence form sensible practice.

…an important epiphany: ‘knowing what you’re doing’ largely involves pretending to know what you’re doing. Or, at least, it does in showbusiness. I choose to believe that it isn’t like that with surgery or nuclear power.

The task ahead of me was to fake a year’s worth of study in about four weeks. And I wasted most of the first week in the pub.

No one can spot an actor’s flaws as quickly and as mercilessly as an out-of-work actor.

Maybe I was just talentless, I thought in dark moments. But then I’d turn on the television, watch a few minutes of primetime and remind myself that talentlessness was no barrier to success.

As I prepared for Edinburgh in 1997, failure felt both unthinkable and inevitable. There’s a lot of crossover between those two qualities – probably because there’s not much point in thinking about the inevitable. That’s my view, at least – I would never have made much of a philosopher or priest.

It took me a long time to realise how little was going on here. I naively thought that people in offices were busy – that if you worked in TV, you were constantly rushed off your feet making programmes or having meetings about programmes you were about to make. Occasionally, I thought, you might find time to squeeze in a chat with someone new, someone promising with no track record, but only in order to get them working on an idea that would, in time, become a TV programme.

The reality is that meeting new people and aimlessly chatting about ideas basically is the TV industry. Hundreds make their living in perpetually salaried ‘development’, seldom troubling a cameraman. Only under exceptional circumstances is a show actually made, at which point the key idea-developers, the ones who have meetings, often delegate that task to others. Our little chats with TV companies had only been about making contact, acknowledging each other’s existence, as part of the vast, inefficient, meandering dance which the comparatively small amount of actual TV production manages to support.

I’m a slightly obsessive ‘goodbye’ sayer – I come away from parties with an unsettled feeling because I haven’t formally taken my leave of all the people I chatted to. I know that’s fine and people don’t expect it, but it feels like I’ve left lots of loose ends hanging.

Getting laughs both for your material and your performance isn’t just twice as good as one or the other. It is roughly 3.2 times as good. I have done the maths on this.

For years I resisted a smartphone because email, I felt, was something that should always be able to keep until I got home. If it’s urgent, let people ring or text. An email is like a letter – people shouldn’t expect a response in less than a day or two. But, if they get wind of the fact that you can receive emails 24/7, the timetable on which they expect a response suddenly shortens.

So my aim is that my appearance should in no way be noteworthy. But then again, not so un-noteworthy as to be in itself noteworthy.

…I always feel a bit guilty – I think feeling guiltless is somehow impolite.

It’s so much easier to talk about what makes you unhappy than what makes you happy, I’m now discovering.