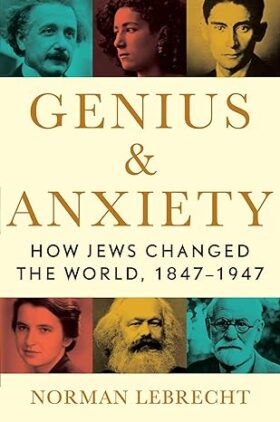

Genius & Anxiety

Author: Norman Lebrecht

Release: December 3, 2019

Tagline: How Jews Changed the World, 1847-1947

Publisher: Scribner

Genre: Social Studies, History, Cultural Jewishness

ISBN-10: 1982134224

ISBN-13: 978-1982134228

Main Character(s): Marx, Freud, Proust, Einstein, Kafka, Ehrlich, Marcus, Franklin, Haber

Synopsis: In a hundred-year period, a handful of men and women changed the world. Many of them are well known—Marx, Freud, Proust, Einstein, Kafka. Others have vanished from collective memory despite their enduring importance in our daily lives. Without Karl Landsteiner, for instance, there would be no blood transfusions or major surgery. Without Paul Ehrlich, no chemotherapy. Without Siegfried Marcus, no motor car. Without Rosalind Franklin, genetic science would look very different. Without Fritz Haber, there would not be enough food to sustain life on earth.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Genius & Anxiety Sets the Record Straight on a Perilous Century

Quotes and Lines

Folk wisdom has it that five Jews wrote the rules of society:

Moses said, “The law is everything.”

Jesus said, “Love is everything.”

Marx said, “Money is everything.”

Freud said, “Sex is everything.”

Einstein said, “Everything is everything.”

Among Jews, anxiety is a primary motivating factor, the engine of fresh thinking.

Today the Internet provides us with access to more information than we can ever need to know, but it cannot supplant the memories of men and women who were brought up to seek truth, conserve it, and, at all costs, defend it.

Poetry, like Torah, is pure. It is not to be used for earthly needs.

Mendelssohn might have ceased to be a Jew, but he can never compose like a goy.

Jews hate silence. They hum and drum while waiting in line, walking in the street, or cooking supper.

Ashkenazi Jews in Europe cannot understand the prayers of Sephardim in North Africa.

Judeophobia is a psychic aberration. As a psychic aberration it is hereditary; and as a disease transmitted for two thousand years it is incurable.

“To succeed in business you need talent,” he tells his hosts, “but if you have such a talent, why waste it on business?”

As for the genizah, Cambridge has no idea how to handle it after Schechter leaves. Some, over the next half century, call for it to be removed or destroyed. A German-Jewish ethnographer, Shlomo Dov Goitein, recognizes it in the 1950s as an unparalleled resource for studying a millennium of social and economic life around the Mediterranean. It is now a treasured part of the library of Cambridge University, accessible by appointment. The chief takeaway for the non-specialist visitor like me is the dynamism it reveals within Judaism, a faith that adapts to all weathers without compromising its core. This is the grail that Schechter has sought, the proof of his people’s resilience.

If ever a novel should not have been written, it is this one.

He is sick and tired of the “Jewish weakness, always anxiously to want to keep the Gentiles [Gojims] in a good mood.” Anxiety is never far from the mind of this Jewish genius.

American Jews, immigrants or sons of immigrants, invent the industries of mass distraction. They are the tastemakers of the twentieth century

The audience, in Schoenberg’s view, is always in the wrong. “If it is art, it cannot be for all and if it is for all it cannot be art,” he announces. Asked if he has given up melody forever, he says: “No, I’m just looking for a different kind of tune.”

A creator has a vision of something which has not existed before this vision. . . . In fact, the concept of creator and creation should be formed in harmony with the Divine Model. . . .”

“Hava Nagila” exists to prove Idelsohn’s point: the tunes most people think are truly Jewish are nothing of the sort.

“The whole sense of the book might be summed up in the following words: what can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we can- not talk about we must pass over in silence.”

He comes alive only after work, he writes: “I devour the hours outside the office like a wild beast. . . . I emerge from the crowdedness of my leisure hours scarcely rested.”

Kafka is Jewish to his core, Jewish in all his work: “Self-evidently, writes the essayist George Steiner, “of the Biblical and Talmudic legacy? Kafka’s Jewish identity is proclaimed in his sense of family, his respect for social justice, his cultural curiosity, his multiple neuroses, above all in his prevailing anxiety-the awareness that something terrible is about to happen and there is nothing anyone can do to stop it. His anxiety is more than just a conditioned response to a history of Jewish persecution. It is a creative distillation of that legacy into something recognizable as genius. Anxiety is the engine of Franz Kafka’s humanity.

“I am proud of being Jewish,” says Tucholsky. “If I wasn’t proud, I’d still be Jewish. So I’d rather be proud.”

“I was born a scientist,” he would say. “I believe that many children are born with an inquisitive mind, the mind of a scientist, and I assume that I became a scientist because in some ways I remained a child.”

A work of history if not written in isolation