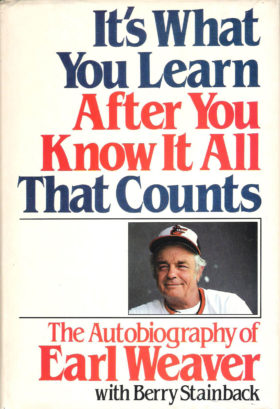

It’s What You Learn After You Know It All That Counts

Authors: Earl Weaver and Berru Stainback

Release: 1982

Tagline: The Autobiography of Earl Weaver.

Publisher: Doubleday

Genre: Baseball, Biography, Autobiography, Philosophy, Non-Fiction

ISBN-10: 0385176503

ISBN-13: 978-0385176507

Declassified by Agent Palmer: “It’s What You Learn After You Know it All” is for Baseball Fans and Managers of all Types

Quotes and Lines

Writers have often found Earl Weaver to be a most complex and controversial individual.

Aggressiveness and positive thinking are keystones of Earl Weaver.

He smokes constantly and refuses to be photographed while indulging in “this filthy habit,” not wanting to influence youngsters.

Earl Weaver is the manager who introduced the use of statistics into the dugout.

“Say, are you home now? You put in a garden this year? Look, Rip just got me a bucket of cowshit for fertilizer. What do you mean you want a bucket of cowshit? You already got enough bullshit for three gardens!”

“Paul Richards said it many years ago,” Earl told the press afterward: “‘You’re never as good as you look when you win. And you’re never as bad as you look when you lose.’”

“You have to keep your distance from your players no matter how much you like them,” Earl says. “You’re the person who decides all the worst things in their lives. You’re the one who has to pinch hit for them, pinch run for them, bench them, trade them, fire them. You know the day will come when you’ve got to look every one of them in the ye-these guys who have given their all for you, who have won all those ball games that have helped you keep your job–and tell them: ‘I’m sorry. You can’t do the job anymore.’ It rips your heart, but it goes with the manager’s office. You can’t help loving them, yet you can’t afford to.”

The reporters drifted off and Jim Palmer sat down next to Weaver. “Jeez, Dempsey’s really down, Earl.,” he said. “Why don’t you have a talk with him.”

“Dempsey pays as much attention when I talk to him as you do,” Weaver said.

“What do you mean? You talked to me after I volunteered to go to the bullpen, and since then I’ve pitched three good games.”

“But did you pay any attention to me?” Weaver asked.

“No,” Palmer said, and they both laughed.

According to the media, I am famous for three things: arguing with umpires, battling with players, and winning ball games. Well, you can’t have the latter without the first two, I’m sorry to say. So the opening chapters in this book will deal with confrontations, beginning with those involving umpires.

I feel obliged to point out that an umpiring crew makes approximately 300 calls per nine-inning game. As I had managed over 2,000 major-league games, I have witnessed more than 600,000 calls. The fact that in this section I’d find fault with only a minuscule percentage of those calls testifies to the splendid job that umpires do overall. It is amazing.

Nevertheless, the names of some of the umpires have been changed or withheld to protect the guilty.

My confrontations with umpires have usually resulted from my attempts to:

- Save a player from ejection by stepping into an argument and saying what the player wanted to say, for it’s far better for me to go than a man who might hit a game-winning home run.

- Wake up an umpire and get him to start concentrating and stop missing calls.

- Get a decision changed that was contrary to the rules of baseball, which the umpires don’t always know.

But there was a game in 1969 when umpire Frank Umont was bound and determined to catch me smoking. He was working third base and looking over at me so often I was afraid he might get hit with a line drive. But at one point I lit up without stepping far enough into the runway, and Umont came running out over and said, “Okay, Weaver, I got you smoking. That’s a fine.”

I said, “My mother lets me smoke, Frank.”

The next day when I took my lineup card to the umpires I was sucking on a candy cigarette. I politely offered the umpires a bite–and Umont threw me out of the game before it even started!

God bless Nestor Chylak’s “cool.” And bless any umpire who “adjusts his mind” and weighs situations and circumstances before acting. Isn’t that what arbiters–whether they sit on a bench in a court of law or work on a baseball diamond–are supposed to do?

Yet it seems like every time an umpire makes a mistake, a manager gets fined or suspended or both.

I heard about a minor-league manager who managed a 1981 game while wearing the tiger suit of his team’s mascot. I’m thinking of donning the Oriole mascot’s Bird suit during my next suspension. Maybe I could “debate” balls and strikes through a beak. Would umpires dare eject the beloved Bird?

Winning is the only meaningful final score, and my desire to do so has been the underpinning of every confrontation. I’ve had them ever since I started managing, and I will have them until I retire.

Oh, was he stubborn! I tried to point out to Rick some fundamental truths. A manager manages. A pitcher pitches. And a catcher receives. We had a big fight on this subject. “Rick, a catcher catches the ball,” I said. “When you’re given more responsibility, we’ll change the title. We’ll call you an executive receiving engineer or something.”

When valid points are made on both sides of an issue, people have got to learn something if they have any sense at all.

My father handled the dry cleaning for both the Cardinals and Browns, and he often took me along with him to pick up and deliver the uniforms. It was a thrill going into the dressing room and seeing all my heroes from the Gashouse Gang and the Browns.

Many of the most successful managers had been mediocre ballplayers like myself because those of us with limited abilities had to think more and play smart baseball to sustain a professional playing career on any level.

No matter how much they tried, there were aspects of the game they would never learn and there were plays they could never make. I worked trying to correct these weaknesses, but in many cases I discovered I simply had to manage around them. The key was never to ask them to do what they could not do–only what they could do.

Loyalty is a good trait, but it is not a good job-keeping trait if it results in your staying with players who can no longer do their jobs on the ball field as well as they had in the past. As a manager, your obligations are to the team you work for and the hell with the people who did things for you yesterday. A manager must live by that hard-hearted cliche: What have you done for me today?

I also posted a sign in the clubhouse that announced a credo of mine: “It’s what you learn after you know it all that counts.”

As Frank Robinson later said, “Nobody can chew you like Earl can chew you, and it’s plenty tough to take. But the instant it’s over, it’s forgotten. The man never carries a grudge. He does the best job of any manager I’ve ever seen at keeping twenty-five ballplayers relatively happy.”

We played equally tough baseball in 1970, winning 40 of the 55 games we engaged in that were decided by one run.

Earl “Class A tops” Weaver was a goddamn World Champion!

You manage according to the abilities at your disposal and don’t ask anyone to do anything he isn’t capable of.

All of this led writers to ask, “Isn’t it nice having all that speed?” To which I would reply, “I’d rather have more three-run homers. Then everyone can take their time and stroll home. I’ve never had a base runner thrown out once a ball’s been hit over the fence.”

Standing there looking at Brooks holding the base with that wonderful smile on his face and the crowd going wild in the background and all of the love and warmth permeating the stadium . . . I thought, I’d like to be like Brooks Robinson. The guys who never said no to anybody, the ones that everybody loves because they deserve to be loved, those are my heroes.

“The Orioles are amazing,” I overheard coach Frank Robinson tell a writer. “A lot of clubs sit down at the end of spring training, pick the twenty-five best athletes, and head north. Here they sit down and look for the right mix, and they do it in detail like no other ball club I’ve ever seen. It’s not just the best athletes or the best starting nine. It’s who can do the best job of sitting on the bench for a week, then go up and get a hit? Who can steal a base as a pinch runner in the late innings? Who can play more than one position if someone gets injured? Nobody in baseball can put all those elements together better than Earl Weaver because nobody can judge baseball talent as well as he can.”

When all is said and done, all I want anyone to say about me is, “Earl Weaver–he sure was a good sore loser.”

Edward Bennett Williams, principal owner of the Orioles, has said that baseball’s hierarchy could “foul up a two-car funeral,” and that was resoundingly demonstrated in 1981.

“I still believe in the words on that sign I hung in the Baltimore clubhouse the day I took over the Orioles: ‘It’s what you learn after you know it all that counts.’ You learn by listening and observing, and you never stop.”

“Managers are always learning,” Earl Weaver concluded, “and mostly we learn from our mistakes. That’s why I keep a list of my mistakes at home for reference. I used to carry the list around in my pants pocket, but I finally had to stop. It gave me a limp.”