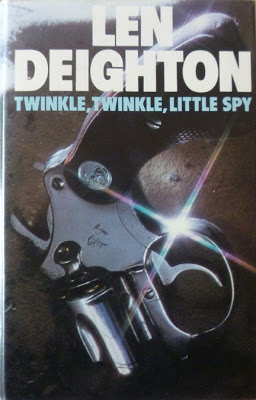

Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy

Author: Len Deighton

Release: June 17, 1976

Alternate Title: Catch a Falling Spy

Publisher: Jonathan Capt Ltd.

Genre: Fiction, Spy Fiction

ISBN-10: 0224012770

ISBN-13: 978-0224012775

Main Character(s): Frederick L. Antony, Colonel Mann, Professor Bekuv, and Red Bancroft

Synopsis: A Russian scientist defects, believing that in the West he will more easily realize his dream of contacting planets in outer space. But British Intelligence and the CIA have more worldly plans for him and move quickly and relentlessly, leaving behind a trail of blood across three continents.

Declassified by Agent Palmer: In Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy, Antony joins the ranks of Palmer, Armstrong, and Charles.

Quotes and Lines

‘I have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night.’

-Epitaph on grave of unknown astronomer

Mann nodded. ‘And do you know something else . . . the way they’re going, in another few years there will be another million stars there–enough spy satellites to put us both out of business.’

‘Twinkle, twinkle, little spy,’ I said.

‘Well, a maser is a laser but a laser is not necessarily a maser.’

Desert travellers have survival in common; never knowing when you might need a friend.

‘Yes,’ I said. My name was Antony; Frederick L. Antony, tourist.

‘There are ways,’ I said. ‘There are official swops as well as escapes. And what you never hear about are the secret deals that our governments do. The trade agreements, the loans, the grain sales . . . all these deals contain hundreds of secret clauses. Many of them involve people we exchange.’

But his worst mistake was in looking forward to the moment when it would all be over; professionals never do that.

I got a sick kind of pleasure from provoking Major Mann, and he rose to that one as I knew he would: he stubbed out his cigar and dumped it into his Jeam Beam bourbon–and you have to know Mann to realize how near that is to suicide.

Her cheekbones were high and flat and her mouth a little too wide. Her eyes were a little too far apart, and narrow–narrower still when she smiled. It was a smile that I was to remember long after everything else about her faded in my memory. It was a strange, uncertain smile that sometimes mocked and sometimes chided but was none the less beguiling for that, as I was to find to my cost.

‘I’m not lucky in love,’ she said. ‘Just in backgammon.’

Backgammon is more to my taste than chess. The dice add a large element of luck to every game, so that sometimes a novice beats a champion, just as it goes in real life.

‘Everything goes right for those in love,’ said the alarm man.

‘My analyst says it’s a subconscious desire to wash my mouth out with disinfectant.’

I polished my spectacles–people tell me I do that when I’m nervous–and gave the lenses undue care and attention. I needed a little time to look at Gerry Hart and decide that a man I’d always thought of as blowing the tuba was writing the orchestrations.

‘You always talk like everyone is on the make. Don’t you ever get depressed?’

Mann straightened and threw his head back. He held the cigar to his lips and put the other hand in the small of his back. It was a gesture both reflective and Napoleonic, until he scratched his behind.

…and I saw Red and Mrs Mann exchange that sort of knowing look with which women greet the downfall of a male.

‘Nostalgia isn’t what it used to be,’ pronounced Mann.

‘There comes a time in your life when you have to do the human thing–make the decisions the computer never makes–give your last few bucks to an old pal, find a job for a guy who deserves a break, or bend the rules because you don’t like the rules.’

‘The better the day, the better the deed. Isn’t that what they say?’

‘You know something,’ he said scornfully. ‘You can be very, very British at times.’

Dean has ‘a drinking problem.’ That had always struck me as an inappropriate euphemism to apply to people who had absolutely no problem in drinking.

But the staircase would defeat me. Dean would know each creaky step, and how to negotiate them but such an obstacle will always betray a stranger.

There was also time to feed two dollars into a jovial robot which dispensed cold cheeseburgers in warm Cellophane and hot, watery coffee in dark-brown plastic cups.

‘I left the ouija board in my other pants.’

‘You’re a lousy loser,’ I told him quietly as I got in beside him.

‘Yeah,’ agreed Mann. ‘Well, I don’t get as much practice as you do.’

The Psychological Advisory Directorate was a cosy assembly of unemployed head-shrinkers who knew how to avoid every mistake that the C.I.A. ever made, but unfortunately, didn’t tell anyone until afterwards.

‘Supposed to mean?’ said Mann. ‘I’m glad you said supposed to mean, because there’s often a world of difference between what things mean, and what they are supposed to mean…’

‘Perhaps he loves her,’ I said. ‘Perhaps it’s one of those happy marriages you never read about.’

‘It’s telling the servants that’s the real trouble,’ she confided.

‘Don’t worry about that,’ said Mann briskly. ‘My friend will do that. He’s British; they’re terribly, terribly good at speaking to servants.’

They are made of marble, steel, chromium and tinted glass, these gleaming governmental buildings that dominate Washington, D.C., and from the top of any one of them, a man can see half-way across the world–if he’s a politician.

I should have obeyed orders. I didn’t, and what happened subsequently was all my fault. I don’t mean that I could have influenced events, it was far too late for that, but I could have protected myself from the horror of it. Or I could have let Mann protect me, as he was already trying to do.

‘Look, pal. My idea of culinary exotica is hot pastrami on rye bread.’

Men become mesmerized by the desert, just as others become obsessed with the sea; not because of any fondness for sand or water, but because oceans and deserts are the best places to observe the magical effect of ever-changing daylight.

I am only interested in pure science–I’m not interested in politics–but in my country to be apolitical is considered only one step away from being a fascist. No man, woman or child is permitted to live their life without political activity . . . and for a real scientist that is not possible.

‘Life is a comedy for those who think–and a tragedy for those who feel,’ I said.

‘Yours is the voice of ignorance and suspicion. Those same thoughts and fears drag civilization back into the Dark Ages. No scientist worthy of the name can put his personal safety before the pursuit of knowledge.’