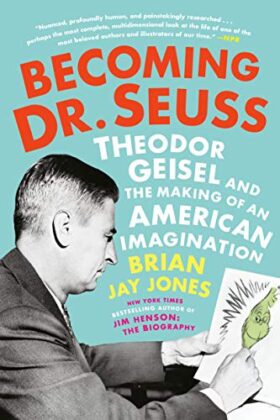

Becoming Dr. Seuss

Author: Brian Jay Jones

Release: May 7, 2019

Tagline: Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination

Publisher: Dutton

Genre: Artist, Author, Biography

ISBN-10: 1524742783

ISBN-13: 978-1524742782

Declassified by Agent Palmer: Take a Look in the Book of the Path Dr. Seuss Took

Quotes and Lines

But before Ted himself, turning minnows into whales was all part of the fun. There would always be a bit of Marco, the teller of outlandish tales, in Theodor Seuss Geisel–and in Dr. Seuss.

But while Ted would accept the status quo, he would never be wildly happy about it.

…Ted was never sure exactly what Maclean was working on in the winter of 1923; the evening Maclean finished his book, he and Ted were out celebrating when Maclean’s boardinghouse burned to the ground, taking the novel with it. “I don’t think he ever rewrote it,” Ted said.

“I began thinking that words and pictures, married, might possibly produce a progeny more interesting than either parent . . . [though a]t Dartmouth, I couldn’t even get them engaged.”

…wasn’t sure his English degree would be good for much of anything, calling it “a mistake” that taught “the mechanics of getting water out of a well that may not exist.”

As a mediocre student who had struggled to attain a C in a general English seminar at Dartmouth, a deep drill into Germanic philology at Oxford–even if taught by the brilliant new professor J.R.R. Tolkien–was bound to be a struggle.

Ted once claimed it ran for two volumes–”and when it wouldn’t sell,” he said years later, “I condensed it into one volume. When that didn’t sell, I boiled it down into a long short story. Next I cut it to a short, short story. Finally I sold it as a two-line gag. Now I can’t even remember the gag.”

Writing for Jester, Cerf explained, “[taught me] how to write a quick story, how to put it down in as few words as possible. . . I learned not to clutter up my mind with a lot of useless information because an intelligent man doesn’t need to carry all that stuff in his head. He has only to know where to find what he needs when he needs it.”

They know no other system than the one that poisoned their minds. They’re soaked in it. Trained to win by cheating… they’ve heard no free speech, read no free press… Practically everything you’ve been trained to believe in, they’ve been trained to hate and destroy.

While he’d never been one to adhere to the edict of “follow your bliss,” he certainly wasn’t inclined to remain in a job that made him creatively and artistically miserable, either.

Censorship forced us into straddling lots of issues that should have been met straight on . . . Certain hunks of history are considered too hot to handle. The industry wants to please everyone and offend no one. That’s how they make money . . . But don’t quote that, or I’ll get fired out of Hollywood.

“Great style is great artistry,” he admitted, “but without a story, great style is spinach,” discarded by kids in the same way unwanted food is pushed off the dinner plate.

. . . there is something we get when we write for the young that we never can hope to get in writing for you ancients . . . Have you ever stopped to consider what has happened to your sense of humor?

“Adults are obsolete children,” Geisel would reiterate later, “and the hell with them.”

The real problem with Hollywood, he groused, “is that all these people work on things, until even the author doesn’t know what’s his and what’s not.”

Throughout his life, Geisel would maintain a regular work schedule, sitting at his desk all day, even if stuck for an idea. “For me, success means doing work that you love, regardless of how much you make,” said Geisel. “I go into my office almost every day and give it eight hours–though every day isn’t productive, of course.”

“Dr. Seuss should stop it; he’s going too far. He’s subversive.” Geisel gleefully agreed. “I’m subversive as hell!” he roared. “I’ve always had a mistrust of adults,” he said later. “And one reason I dropped out of Oxford and the Sorbonne was that I thought they were taking life too damn seriously, concentrating too much on nonessentials.”

“I think writing is the worst job that anyone ever got into,” Helen wrote sympathetically.

(“people who think about endings first come up with inferior products,” he groused).

“I have a secret following among adults, but they have to read me when no one is looking,” said Ted.

The Lorax was written in anger–”one of the few things I ever set out to do that was straight propaganda,” he said later…

“I’m naive enough to believe that society will be changed by examination of ideas through books and the press,” Geisel said, “and that information can prove to be greater than the dissemination of stupidity.”

“Kids who have no interest in books are usually from slob parents who themselves had no interest in books,” said Geisel. “The trouble is, the hour parents used to spend reading to their kids is now spent drinking martinis which, let’s face it, is more fun.”

Standing at the window of his studio with one journalist, Geisel gestured at the beach below. “Those are some of my retired friends down there, but retirement’s not for me!” he said. “For me, success means doing work that you love, regardless of how much you make. I go into my office almost every day and give it eight hours-though every day isn’t productive, of course.”

As you partake the world’s bill of fare,

That’s darned good advice to follow.

Do a lot of spitting out the hot air.

And be careful what you swallow.

“People of my age are all retiring, which is something I would never want for myself,” Geisel told The Saturday Evening Post.

“He rants and rails at the change,” noted Audrey, “but man does not live by cholesterol alone, although he sometimes dies by it.”