I’ve prided myself on separating the artist and their art. On a whole, it generally makes things easier to enjoy.

The art is the art, and any baggage that may come with the artist can be left at the door.

There is an exception that changes the perception of the artist and can change the art, which is based on digging deeper into the artist. When you read a biography, watch a documentary, or most specifically, read an autobiography, it can and often does change your perspective on the artist and by extension the art. Thankfully, for me it’s only one way.

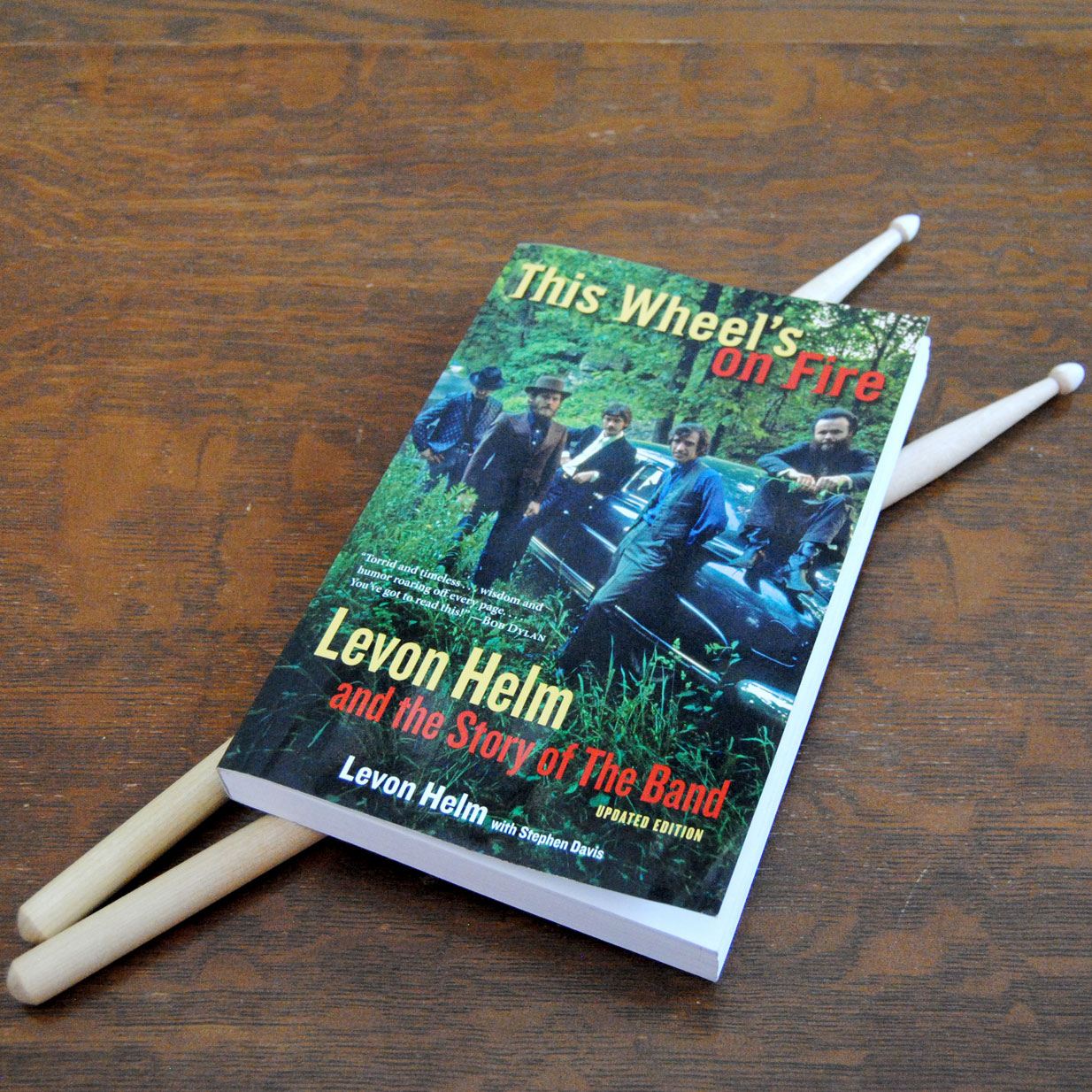

I can also hold two seemingly disparate feelings about the same piece of art. These are some of the thoughts and emotions that I had after finishing This Wheel’s on Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of the Band, a final epilogue of sorts by Levon Helm with Stephen Davis.

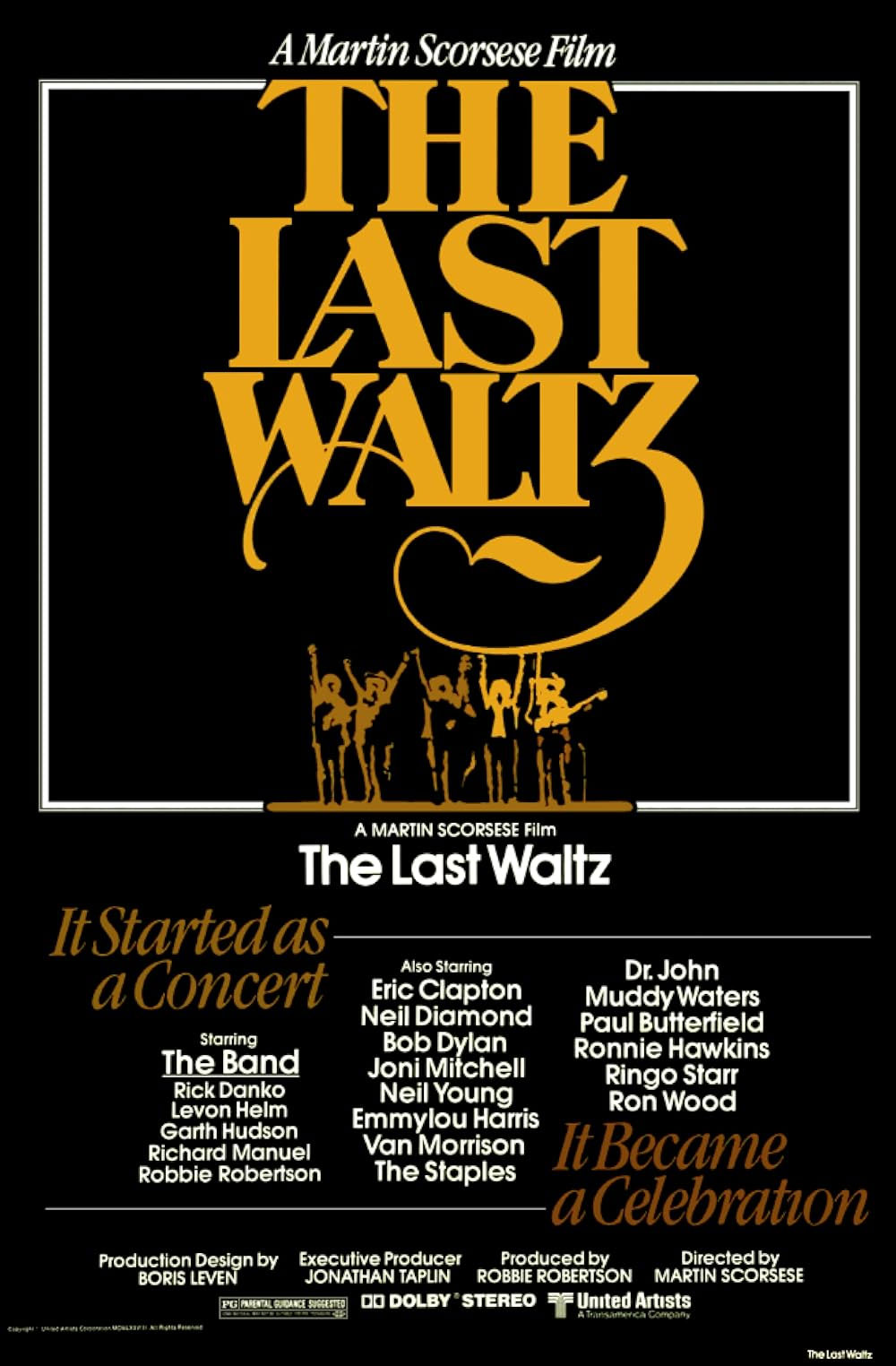

Don’t get me wrong, I still love The Band, and I will continue to enjoy The Last Waltz. To know that their run didn’t have to end and that success turned out to be an enemy of sorts definitely change the perspective. So, too, does the reason for Levon’s autobiography, written in Davis’ epilogue pretty matter-of-factly:

“The Band’s story had been “owned” by Robbie Robertson. He had been the group’s public spokesman from the 1968 debut of Music from Big Pink to The Last Waltz in 1978, and then on through the publicity around his early solo career in the 1980s. For Levon, this book developed into an opportunity to reclaim the group’s history from a different perspective–the drummer’s chair, the best seat in the house. It was his last chance to tell a different version, closer to the truth, about some crucial issues that had been buried or ignored in the semi-official propaganda that had entered the canon as the accepted story of The Band.”

I’m guilty of buying into the propaganda. I always thought that The Band threw The Last Waltz as a great farewell concert to go out on a high. It had never occurred to me that Robbie Robertson wanted to stop and that, through managements’ and agents’ “divide and conquer” strategy, ended up with more than his fair share and chose to stop, despite the rest of The Band wanting to continue.

In fact, from the stories told by Levon, and especially those that come from the other members, most notably and poignantly from Rick Danko, you get the idea that Robertson was the only one who wanted to say goodbye.

Given that most of the members of The Band chose to continue on without Robertson as far as touring is concerned, you can easily surmise that Helm’s version of the dissolution is more accurate. If that’s the case, wouldn’t you also give more credence to his version of the whole complete story of The Band?

From his Arkansas roots to the barnstorming, bar-hopping, rocking Ontario nights, through to Woodstock, N.Y., Malibu, Calif., and many stops in between and around the world, Helm and Davis seem to cover the origin of The Band, the roots and threads of American music, and the grim reaper of The Band’s “success.”

This book is written conversationally. It is a conversation with Levon, and he pulls absolutely no punches.

For that reason alone, it’s worth picking up. If you need another, just know that The Band’s influence, which isn’t really discussed in this book, is so far-reaching that this will give you a base understanding of where they come from, and where their music and their soul comes from. This base will serve you well when you read and hear other musicians discuss how The Band influenced them.

Besides, how often do you get to have a conversation with one of the greatest voices to ever sit on a drum stool? And posthumously at that! Plus, if you stop to listen to the music every so often, you’ll realize just how amazing the soundtrack to this book could be!

Read the Secret File of technical information and quotes from This Wheel’s on Fire.