To succeed in many fields, it’s very important to have a base knowledge of the history within that field. Doctors learn about the history of medicine, writers learn the origins of the written word, and mechanics learn the basics behind the machines they’ll be working on.

However, it struck me as odd, that as a blogger and professional web guy, that I didn’t have more than the faintest idea of the history of the Internet, which is where I make a considerable portion of my income, professionally and otherwise.

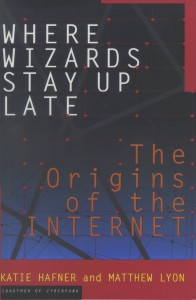

It was with that reasoning, that I picked up Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet by Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon. From the creation of ARPA – which led to ARPANET and the many protocols, functions, and programs that forwarded technology into the Internet as we now know it – to Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), now BBN Technologies, the mother of the early ARPANET – this book covers it all.

At times the book is academically dry, but the characters who helped bring about something that too many people take for granted, are fantastic, and, well, real. And if you’re looking for an idea as to who these people really are, I refer you to the following two passages from the book.

“At the same time, the growth of the network gave rise to a new problem. ‘When we got to about two thousand hosts, that’s when things really started to come apart,’ said Craig Partridge, a programmer at BBN. ‘Instead of having one big mainframe with twenty thousand people on it, suddenly we were getting inundated with individual machines. Every host machine had a given name, “and everyone wanted to be named Frodo,’ Partridge recalled.”

“The NWF [Network Working Group] was an adhocracy of intensely creative, sleep-deprived, idiosyncratic, well-meaning computer geniuses.”

So they could easily be compared to the gamers and social network users that spend countless hours connected to each other on the very network spawned by these geeks and nerds, all of whom, or at least most of whom, enjoyed Tolkien enough to want to give their host machines the name of Frodo.

The most fascinating character of all the players mentioned in the book is J. C. R. Licklider, known as “Lick,” who was around for the conception of the idea. He was the guy who shifted ARPA’s emphasis from computing command systems “playing out war-game scenarios to advanced research in time-sharing systems, computer graphics, and improved computer languages.”

And Lick’s vision of “the concept of the Intergalactic Network to mean not just a group of people to whom he was sending memos but a universe of interconnected computers over which all might send their memos,” was something that has indeed come to pass.

Meanwhile, the success of ARPANET didn’t turn over to the Internet right away. There will still plenty of protocols and programs and even languages to be created and decided upon.

Why protocol? “‘The other definition of protocol is that it’s a handwritten agreement between parties, typically worked out on the back of a lunch bag,’ Cerf remarked, ‘which describes pretty accurately how most of the protocol designs were done.'”

At this point ARPANET was still the wild West, with rogue programs and everyone using it as they saw fit. In the group of users, there was a conversation about the first two applications. “As the talks grew more focused, it was decided that the first two applications should be for remote log-ins and file transfers.”

And as basic applications for a new network people were still getting familiar with, one can’t argue with the conclusion they came to.

“Then again, technological advances often begin with attempts to do something familiar. Researchers build trust in new technology by demonstrating that we can use it to do things we understand. Once they’ve done that, they next steps begin to unfold, as people start to think even further ahead. As people assimilate change, the next generation of ideas is already evolving.”

As ARPANET continued to grow, the idea of official protocols, programs, and communications started to become a harrowing argument. “Proclamations of officialness didn’t further the Net nearly so much as throwing technology out onto the Net to see what worked. And when something worked, it was adopted.” This is still true to this day. Nothing is officially adapted because a proclamation is made, it is adapted because the users like it and utilize it, or it is abandoned and forgotten.

As electronic mail became more and more widely accepted and used on ARPANET, Paul Baran and Dave Farber made a statement in a paper that would come true, albiet not immediately.

“‘Tomorrow, computer communications systems will be the rule for remote collaboration’ between authors, wrote Baran and UC Irvine’s Dave Farber. The comments appeared in a paper written jointly, using e-mail, with five hundred miles between them. It was ‘published’ electronically in the MsgGroup in 1977. They went on: ‘As computer communications systems become more powerful, more humane, more forgiving and above all, cheaper, they will become ubiquitous.’”

And the primary means for computer communications was at that time electronic mail. It was by far and away the most widely used application on ARPANET, although there were plenty of issues with protocols and standards that were ironed out to ultimately deliver the email we understand today. There were many numerous programs for sending and receiving mail within ARPANET and it took a while for all of them to be able to communicate with each other. But there were bigger standards issues than how much information should belong in an email header.

Networking took a giant leap forward with the introduction of TCP/IP. But it almost wasn’t the standard for interoffice networking that became widely used. There was a rival system know as OSI that was being backed by the government. “‘Standards should be discovered, not decreed,’ said one computer scientist in the TCP/IP faction. Seldom has it worked any other way.” And in fact, this was correct, because the only reason TCP/IP won out was because the users migrated towards using it. If they had adapted OSI, TCP/IP would have died.

But for as amazing as the story is, the shortest synopsis of the process for creating the Internet comes from a speech given by Danny Cohen;

“In the beginning ARPA created the ARPANET.

“And the ARPANET was without form and void.

“And darkness was upon the deep.

“And the spirit of ARPA moved upon the face of the network and ARPA said, ‘Let there be a protocol,’ and there was a protocol. And ARPA saw that it was good.

“And ARPA said, ‘Let there be more protocols,’ and it was so. And ARPA saw that it was good.

“And ARPA said, ‘Let there be more networks,’ and it was so.”

Truth be told, good things can come from government. “The network was built in an era when Washington provided little guidance and a lot of faith.” Maybe that time has come and gone, but it gave us the Internet as an example of what good the government can do when they put trust in science. It’s the same framework and time frame in which science helped the US put a man on the Moon. So maybe it’s not all gone, but we certainly have strayed a long way from those days.

I’ve given you a detailed synopsis but the book gives further detail and introduces all the players, of which there are many.

“’The process of technological development is like building a cathedral,’ remarked [Paul] Baran years later. ‘Over the course of several hundred years new people come along and each lays down a block on top of the old foundations, each saying, ‘I built a cathedral.’ Next month another block is placed atop the previous one. Then comes along an historian who asks, ‘Well, who built the cathedral?’ Peter added some stones here, and Paul added a few more. If you are not careful, you can con yourself into believing that you did the most important part. But the reality is that each contribution has to follow onto the previous work. Everything is tied to everything else.'”

If you exist on the Internet in a capacity to make money or have a hobby you’re passionate about online, you should read this book and learn about the businesses, universities and colleges, government agencies, and individuals who made the Internet possible.

Because without them, all of them and their individual contributions built on those before them, the Internet as we now know it might not exist…

Class dismissed.