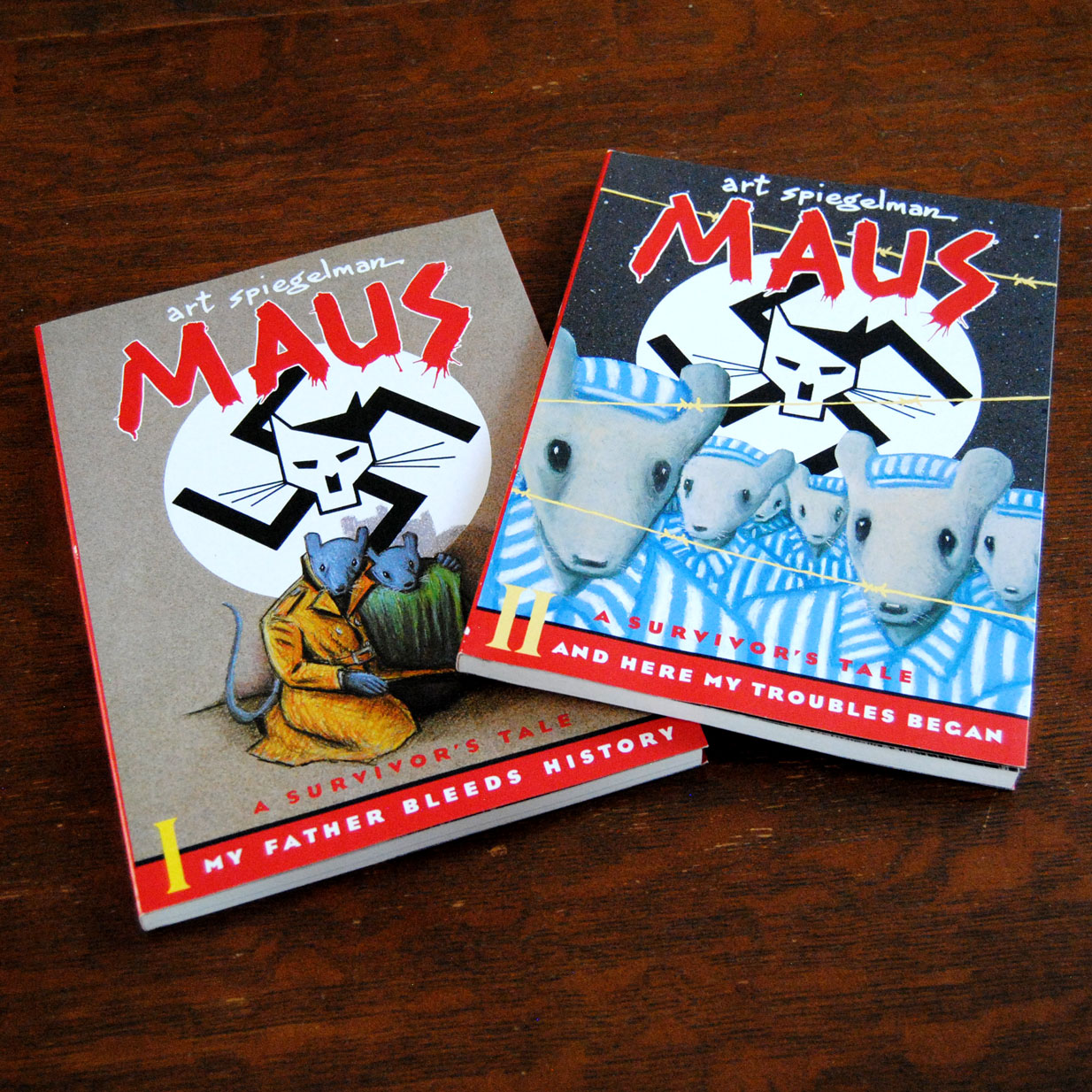

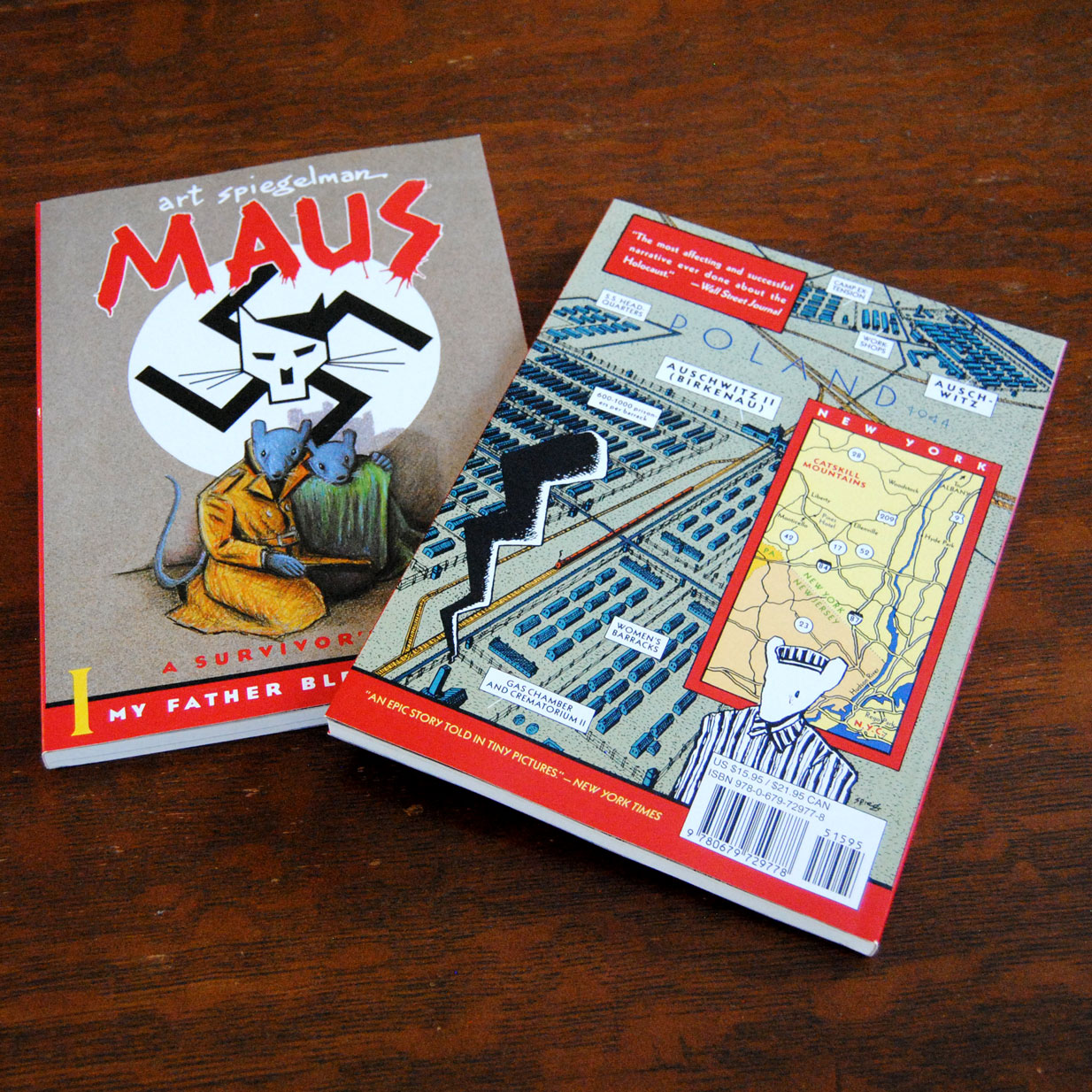

Maus is the award-winning graphic novel by Art Spiegelman. It is a “Survivor’s Tale” specifically, Art’s dad, Vladek, and his survival of the Holocaust.

It is also Art’s story of dealing with his father’s history, legacy, and guilt. It is beautifully crafted in both form and function, in the black-and-white panels, text, and spaces in between.

More personally, Maus was a gift from a friend that took me years to finally read. (Sorry, Bill!) I always thought I had a good excuse. “It’ll be too heavy.” Not really. Not any more than any other World War II book, of which I’ve read more than my fair share. “I’m not ready.” Who cares? This was my most common reason and the least reasonable of the bunch.

I finally added it to my reading list. When it came time, I still hemmed and hawed a bit, but ultimately, I did read it.

And do you know what? It deserves all the accolades it received. It tells more than one generational story while telling a single family’s struggle for survival in more ways than one. And it also does so in such a familiar way.

Maus feels like a story I know by heart, even thoughI’ve never read it before. While reading the second volume, I came to a conclusion. The copy Bill gifted me broke the complete story into two volumes: Maus I: My Father Bleeds History and Maus II: And Here My Troubles Began.

What I figured out, in my own brain, is that while Maus is a unique story told straightforwardly, for some of us, it is universal. It has the beats and rhythm of the stories my grandparents told. It also is a little bit like how the genetic sequencing is described in Jurassic Park. (Hang on, it’ll make sense.)

You see, as the movie describes, the Jurassic Park scientists have most of the DNA sequences for the dinosaurs. In this way, Maus is most of the sequence or story.

In the movies, they use frog DNA to fill in the holes. In regards to this unconventional metaphor, the frog DNA that fills in the holes and completes the sequence is my own Jewishness. My cultural upbringing as a Jew and the albeit light but abundant religious and historical education I received fills in all the holes.

For me, that’s what makes this story so familiar. Put another way, Maus is a story told in black and white, but my cultural and religious familiarity with the subject matter adds color to it. I know this story because it is mine. Yes, many of the stories you hear from Holocaust survivors are similar. Because I’ve learned about the war, the occupations, pogroms, the numbers, the survivors’ guilt (sometimes acknowledged, sometimes not, and always present), I know this story.

Holocaust survivor stories and their often-associated guilt are similar to the story of Passover, at least to me. When the Torah describes the Four Children who ask questions about the Exodus, it’s the answer to the “child who does not know how to ask” that comes to mind.

“And you shall tell your child on that day, ‘We commemorate Passover tonight because of what God did for us when we went out of Egypt.’”

This is, to me, why Maus feels familiar, why I’ve learned what I have and know what I know. Every story is a commemoration of that struggle and that survival.

Maus is a triumph in that it captures more than survival; it captures the struggle. What remains passed down in the stories. That it itself is a passed-down story from father to son is part of its brilliance, and that it is passed down further from author to reader is important.

Perhaps I would have eventually stumbled upon this masterpiece on my own, and perhaps I wouldn’t have. I thanked Bill at the time for such a gift, but I need to thank him again and apologize profusely for taking so long to read it.

It’s Spiegelman’s story, sure, but it’s my story too. And it is important and worth sharing.